Yacco's legend

Translated from the book YACCO L’huile des records du monde by Xavier Chauvin.

HISPANO-SUIZA, parent company

In 1904, the Swiss engineer Marc Birkigt (1878-1953) founded in Barcelona the Hispano-Suiza Fabrica de Automobiles S.A. company, partnering with two Spanish businessmen, Damian Marteu and Francisco Seix. This ambitious company aimed at producing luxury cars. The firm decided to set up in France in 1911 when the country had one of the largest automobile industries in the world.

In 1904, the Swiss engineer Marc Birkigt (1878-1953) founded in Barcelona the Hispano-Suiza Fabrica de Automobiles S.A. company, partnering with two Spanish businessmen, Damian Marteu and Francisco Seix. This ambitious company aimed at producing luxury cars. The firm decided to set up in France in 1911 when the country had one of the largest automobile industries in the world.

The Great War put a temporary end to Marc Birkigt’s dreams of expansion, while the Hispano factory in Bois-Colombes was placed under the control of the French aircraft engine manufacturer Gnome et Rhône.

Despite these difficulties, the brilliant Helvetian technician managed to sell to the French army new types of plane engines, of which twenty-five thousand units were produced before 1918. The main part was subcontracted to Renault or Lorraine-Dietrich.

As peace returned, the company faced a sudden drop in orders. The factory spread again in the automotive sector, but hoped to diversify into commercial aviation also.

Creation of OMO

Hispano’s administrators wanted to create a subsidiary dedicated to the manufacturing of machine tools and to the distribution of tools and lubricating oils. OMO (standing for Outillage et Machines-Outils in French) was registered in the Commercial Register of the Seine on December 20, 1920. The successful businessman Jean Dintilhac was appointed chairman of the new company.

The development of OMO proved to be a challenge. The French industry faced a concerning crisis after 1918. The fledgling company tried to impose itself in a difficult environment, while most of its competitors, better established, were on the verge of bankruptcy.

First fiscal year’s revenues

Overall revenues: 512,853 French francs (227,526 French francs for lubes).

Machine tools: - 23,706 French francs.

Tools: - 49,250 French francs.

Lubes: + 80,239 French francs.

Yaccolines’ rise

The company mainly focused on the supply of lubricants, while ancillary activities were dwindling rapidly. The development of automobiles and road transports led to a significant need for lube. Garages bloomed on roadsides. The aviation industry also required quality lubes meeting the requirements of increasingly powerful and sophisticated engines operating at very high speeds. Preferred partner of Hispano-Suiza, OMO distributed more and more lube under the Yacco brand, as Jean Dintilhac had deposited the name in August 1920 (he had already registered "Yaccolines" in November 1919). The general public liked the American sounding of this word derived from the last syllable of his family name.

Yacco products quickly established their reputation for quality and reliability to professionals. The company exhibited for the first time at the Salon de l’auto in Paris in 1923. Jean Dintilhac began to build relationships with carmakers such as Salmson, a leading engine manufacturer and renowned aircraft engines manufacturer. He sponsored an employee of the firm, Mr. Thevenet. Amateur pilot, he used his personal Amilcar during local car racings. Painted in Yacco’s colors, the modest cyclecar achieved some success. Visionary, Jean Dintilhac early foresaw the growing importance of advertising through its best medium: competition.

The unstoppable rise

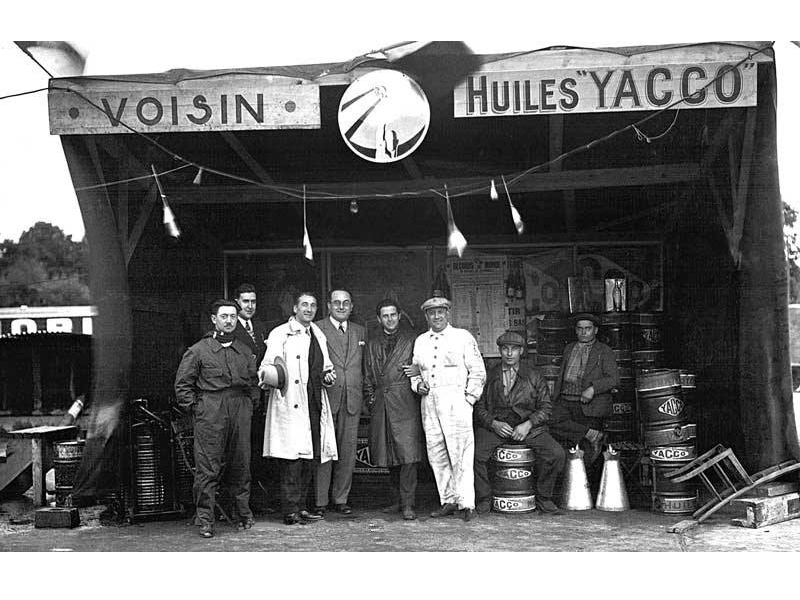

The company kept expanding, bringing its capital to 2 million French francs in March 1924. It changed location to larger premises in Courbevoie. At the same time, the board of directors welcomed several additional members: Emile Mayen, as new Chairman; Alfred Gerson, as new deputy Chairman and Jean Lacoste, all appointed for six year. René Martinat, Secretary, and Pierre Forgeot soon joined them. Leading political figure, the latter is Member of Parliament for Marne department. The charismatic Jean Dintilhac maintained his leadership position in the company, which he still ran with the same panache. He could pride himself on having among its clients the prestigious Voisin, prominent French aircraft manufacturing company.

Tirelessly canvassing manufacturers, the relentless Jean Dintilhac managed to get exclusive contracts with small brands arising from the new trend for cyclecars, such as Benjamin, BNC, Derby, Amilcar or Vinot-Deguingand. Magnat-Debon displayed a sticker on the tank of its motorcycles: "Yacco lubrication only". However, Jean Dintilhac faced "recalcitrant manufacturers" (sic), like Peugeot, Lorraine-Dietrich or Hotchkiss, which refused any partnership with the firm.

The factory beat sales records: for example, it sold in September 1924 a total of 2,016 cases, 329 barrels and 68 kegs (one case usually includes ten to twelve cans of 2 liters, a barrel has a capacity of 200 liters and a keg of 60 liters). The turnover continued to skyrocket: 1,841,860 French francs in 1923; 4,577,612 French francs in 1924 and more than 8 million French francs in 1925. In November 1924, Yacco considered the installation of a new ultra-modern production site in Rouen. With an unfading ambition, Jean Dintilhac entered at the end of the year into negotiations with André Citroën, whose supplier was however the competitor Mobil. The brand located at the Quai de Javel in Paris had the wind in its sails and Yacco was very hopeful about a partnership with the "enfant terrible" of the French automotive industry.

The climax

In April 1926, the firm changed its name. OMO disappeared for good, fading before the new "Yacco SAF" (standing for Société Anonyme Française). A second capital increase took place in November 1928, reaching 4.5 million French francs. The headquarters was moved to the 44 rue de la Grande Armée in Paris’ 16th district. The same year, a new factory was inaugurated in Aubervilliers. In January 1929, Louis Birkigt, Marc’s son, joined the Board of Directors.

Voisin adopted Yacco’s lubes for good, as well as Donnet. The Yacco-Donnet and Yacco-Voisin lubes were distributed through authorized agents. Icing on the cake, Giuseppe Campari’s Alfa Romeo 6C 1750, lubricated by Yacco, won the Mille Miglia in 1929.

If the automotive industry was working well, aviation was not far behind. The partnership with Hispano-Suiza blossomed: the flying stork brand company seold under its own name 20-liter cans conditioned by Yacco. Jean Dintilhac multiplied contacts with Caudron-Renault, Farman, Blériot or Nieuport-Delage. Despite encouraging results, Jean Dintilhac had trouble landing big contracts with the French air Force. In October 1930, Emile Mayen and Alfred Gerson resigned. Marc Birkigt and Pierre Forgeot took over them and were appointed Chairman and Vice-Chairman: the company was even more closely linked with the area of aviation, which was then undergoing an unprecedented expansion.

Voisin and the World Records

Nonconformist, Gabriel Voisin was undoubtedly one of the most prominent personalities of the Parisian high society in the Roaring Twenties. He counted amongst his intimate friend Rudolf Valentino, Mistinguett or Le Corbusier, who frequently drove a Voisin car. In 1925, these atypical automobiles cars were the first vehicles to be part of the speed records organized by Yacco on the ring of the Autodrome de Montlhéry, with a modest four-cylinder motor car coated with a streamlined body.

This car raced between November 6, 1925 and February 22, 1926, beating "seven world records", said the advertisement. Its eight-cylinder successor was even more ambitious, running on the speed ring from April 12, 1927 to January 12, 1928. It ran during twenty-four hours at an average speed of 182.66 kph, winning the hour record at 206.558 kph. Two impressive twelve-cylinder vehicles took over it. The first also won 19 records in its category; the second was a series-produced car which covers more than 50,000 kilometers from September 7 to 25, 1930.

Gabriel Voisin, fond of original technical solutions, commercialized valveless engines exclusively, like Panhard or Peugeot for its most luxurious models. Less noisy and more flexible, valveless engines required however an astronomical lube consumption of about half a liter per 100 kilometers. A plume of blue smoke came from vehicle, which was unfortunately quite revealing! Using quality lube was critical to ensure the longevity of mechanics. Nevertheless, conventional engines were about to make great progress and supplanted definitively valveless engines in the late 1930s.

Rosalie’s successes

In the early 1930s, Yacco underwent a series of disappointments with its key customers as it faced severe financial difficulties: the agreements with Amilcar, Donnet or Voisin were all terminated. For several years, Jean Dintilhac had been courting André Citroën, still under contract with Mobiloil. A B14 taxi was tested over a long period using Yacco lube : it proved less wear after removal of its major mechanical components. Jean Dintilhac obtained from Citroën a C6 F chassis in order to try to beat new records on the Montlhéry speed ring. Rather impervious to this kind of event, André Citroën had a clear preference for long road raids, like the famous cruises. César Marchand, former pilot of Voisin records, used his persuasiveness to convince him to participate in this adventure.

Purchased by Yacco at the beginning of 1931, the C6 F was brought into César Marchand’s workshop at Issy-les-Moulineaux, where it was equipped with a streamlined aluminum bodywork. The team included several pilots who used to take turns every 500 km: Raphaël Combette and Louis Leroy de Présalé, in addition to César Marchand and his brother Julien. This very special C6 F competed in D category, which is reserved to vehicles with a cylinder capacity between 2,000 and 3,000 cm3. Called "Rosalie", the racing car rushed into the race from October, 22 through November 1, 1931. Rosalie I beat fourteen international records, running at an average speed of 108.511 kph during 222 hours, 38 minutes and 56 seconds.

Encouraged by this success, Jean Dintilhac bought a chassis from the new C6 G, immediately prepared for the same purpose. Rosalie II ran during fifty-four laps, from March 5 through April 29, 1932, before breaking its Bakelite pinion. It set again a multitude of new records, covering more than 100,000 km in forty days, at an average speed of 104.331 kph. Rosalie II was therefore the first French car to beat such a distance at such a high speed.

André Citroën, very guarded on Yacco’s initiative until then, exulted after these promising results. He told the press he was willing to offer a one million French francs reward to whoever could beat Rosalie II by October 1. This was an impossible challenge to take up in such a short time, what the owner of the Quai de Javel knew perfectly well. Built on the basis of the new 15 Légère, Rosalie III entered the track on April 6, 1932. Rosalie III was then renamed Rosalie V, as the number IV had been given to the Petite Rosalie in the meantime. Rosalie V continued to collect records, dethroning repeatedly those established by the Voisin two years earlier. It kept running while the little Rosalie entered the track...

When Petite Rosalie became part of the legend

Rosalie IV appeared as the most illustrious representative of the lineage. It used the smallest chassis 8 CV of the Citroën range and thus competed in the F category. The vehicle entered the Montlhéry track on March 15, 1933 and stopped eventually on July 27. During 133 days, the frail Citroën covered nearly 300,000 km at over 93 kph on average, supervised by five marshals and eight timekeepers from the Automobile Club of France. On March 18, it was grounded for six hours due to heavy snowfall. It still managed to catch up with its competitors thanks to the dexterity of its drivers. It turned out to be a remarkable feat, expertly prepared by César Marchand’s team.

As with previous records, the car had to carry in its boot a multitude of spare parts, as described in the extensive inventories of the time: forty spark plugs, three valves, forty-one segments, a spare wheel, three grease guns, three petrol hoses, two hose clamps, two petrol pumps, an engine front support, six radiator hoses, two fan belts, six dynamo coals, a lube boom, a spring caliper, two brackets of shock, a complete shock absorber, two headlight bulbs and their glass, nineteen spring leaves, one half-bit valve collet and three latches...

The Rosalie phenomenon got bigger over the weeks. In light of this fast-growing success, André Citroën started to show some optimism, prompting César Marchand to try to reach the 500,000 km stage.

Advertising impact

Extremely talented in communication, André Citroën decided to stage lavishly this event. A sumptuous reception took place on the racetrack. He glowingly declared in front of the reporters that he was willing to offer 3,000,000 French francs to anyone that could beat Petite Rosalie’s record by July 1, 1935. The carmaker posed with Jean Dintilhac before the Petite Rosalie and gave a warm embrace to César Marchand, to whom he offered a brand new 15 Légère sedan, the top-of-the-range of the double chevron brand at that time. César Marchand then led many conferences organized by Citroën or Yacco, during which were broadcast short films comparing the record attempt to an epic. The record-breaker car, loaded on a special truck, began a huge advertising tour in France. Posters, signs and flyers of all sorts recounted its performance. Citroën built thousands of miniature toys bearing its image. It proved to be a huge success...

This renown predictably rained down upon Yacco, which drew considerable prestige from it. Nevertheless, speed records put a strain on the small lube company’s funds. André Citroën, heavily in debt, struggled to cover the costs he had agreed to pay. Notwithstanding the promise he had made, André Citroën renewed its partnership with Mobiloil, in spite of the media success of Rosalie.

The debts of the company became increasingly burdensome. The jewel of the French car industry was close to bankruptcy. Citroën owed more than 160,000 French francs to Yacco which suspended all its deliveries early 1934. The Quai de Javel factory eventually came under the control of the Michelin brothers, who put André Citroën away from the management board. Mobiloil remained the main provider of the factory, to the great displeasure of Yacco who lost one of its most promising partnerships.

Side records

The effects of the Great American Depression began to be felt in Europe. Business was far from booming, and many small manufacturers until then loyal to Yacco were forced to close down. Nevertheless, 1933 and 1934 remained golden years in terms of records. Jean Dintilhac multiplied rather successful attempts. Maurice Dollfus, chairman of Ford SAF, joined the Board of Directors: Yacco forged close ties with the American company, which was about to enter into partnership with the Alsatian businessman Emile Mathis. Not long before the launch of the Petite Rosalie, Jean Dintilhac hired the Agathe from March 6 to 14, 1933. This is a big Ford 19 CV equipped with a generous 3.3-liter four-cylinder engine which won ten international records.

A 15 CV Légère called "Rosalie VI" added seven new international records to its hit list, between April 7 and 9, 1934 - it exceeded 180 kph in top speed, making it the fastest Rosalie ever timed -. It breaks the records of its only serious competitor of the moment, the curious Citroën 15 CV Spido.

Yacco developed contacts with the countries of the Little Entente, such as Czechoslovakia. He hoped to supply lube to Skoda – which, as reminder, was founded with French capital -, and planned to run a Skoda in Montlhery. Due to a lack of conclusive results, the idea was soon abandoned, although Yacco managed to handle some business with its local counterpart, the Apollo lubes.

Coming together with PeugeotDespite problems encountered with Citroën, Yacco continued to run several Rosalie in Montlhery. Rosalie VII raced from July 17 to 23, 1934. In addition to the wealth of records collected, this Rosalie had the distinction of being the first in the line to use a four-wheel drive (in this case a Coupe 7 CV). Rosalie VIII which succeeded it from July 22 to 29 1935 is still an old 15 CV which had been equipped with a compressor, with the willingness to defeat definitively the 15 CV Spido. It maintained exceptional average for that time, reaching 15,000 km at nearly 145 kph on average.

Jean Dintilhac came closer to Peugeot. He acquired a chassis 301, equipped with the smooth 1465 cm3 of 37 hp. The car was immediately left with César Marchand, who coated it with a roadster body, light and elegant. It was thus able to reach 110 kph in top speed. Both men want to introduce a new form of records by taking out the nice Peugeot called the "Delphine" on an open road. It began its journey on January 2, 1935 and traveled 100,000 km at an average speed of approx. 60 kph; the route included stops at major Peugeot dealers. To top it all, the Delphine finished its tour of France by performing 10,000 kilometers in Montlhéry from September 12 to 16, grabbing some records on its way, as it predecessors used to do.

The popularity of road records

Positively welcomed, the odyssey of the Delphine encouraged Jean Dintilhac to repeat the experience. Performed on an open road, this type of record turned out to be less spectacular but more accessible to the public. César Marchand’s team, backed by Peugeot and Citroën dealers, repeated the same performance in 1936 with Delphine II and Rosalie IX, simple sedans 402 and 11 CV front-wheel drive. These vehicles ran at over 100,000 km, with stages of 1,500 kilometers per day.

Finally, Jean Dintilhac organized in 1937 the last attempt of record on a Citroën: from July 22 to 31, a curious Yacco Spéciale entered the speed ring of the Autodrome de Montlhéry. It is actually a Rosalie fitted with the ephemeral Diesel engine, briefly commercialized by the manufacturer at the same period.

In the meantime, Anthony Lago, who bought Talbot, got in touch with Yacco. The attractive Anglo-Italian, spurred by the prestige of its productions - the Talbot are among the most beautiful sports car of that time -, is willing to recommend Yacco lubes provided the oil company supplied the lubricant for free and granted a premium of 50 French francs to each car leaving the factory. As could be expected, the deal did not come to a successful conclusion...

The Claire, a women’s business

The imposing Claire threw itself into the Montlhéry track on May 18, 1937. It was a Matford equipped with a generous V8 Flathead of 3631 cm3, registered in category C (3,000 to 5,000 cm3). The originality of this last attempt to break a record on slow track lied in its crew, made up of the best female pilot of the time: Odette Siko (team captain), Simone des Forest, the whimsical Helle Nice and Claire Descollas. Her name was drawn to baptize the car. For ten days, the big Matford ran on the speed ring at over 140 kph on average, catching again ten world records and five international records.

Motorcycles records

Talented engine company, Gnome & Rhône, specializing in aircraft engines, was also a renowned motorcycle manufacturer. The company, closely linked to the French army, wished to demonstrate the robustness of its machines by organizing spectacular raids. Yacco, which already used to provide lubricants for aviation branch, immediately joined the project. Very involved in the competition, Gnome & Rhône hired in September 1936 one of its best drivers, the reckless Gustave Bernard, on the tracks of the legendary Orient-Express. Harnessed to a sidecar, the big 750 X connected Budapest to Paris - a distance of 1,519 km - in a little less than twenty-four hours, arriving nearly an hour ahead the famous train, considered one of the fastest of its time.

Spurred by this success, Jean Dintilhac launched the Gnome & Rhône in the assault into the ring of Montlhéry. Several campaigns are organized between 1937 and 1939, according to a recipe that had already proven itself. The motorcycle traveled 10,000 km between June 2 and 6, 1937 at 109.20 kph on average, making sure drivers of the brand but also (and this was a first) officers of the motorized army units were cooperating. On October 14, 1937, the 750 X beat the twenty-four hours at 136.536 kph. Another campaign took place in 1938: between June 30 and July 5, Gnome & Rhône covered more than 20,000 km, winning the 4,000 km record at an average speed of 116.26 kph.

Final attempt on the eve of war (from June 19 through July 8, 1939), the ever valiant 750 X reached 50,000 kilometers at 109.38 kph. Harnessed to a sidecar (with drive wheel), this excellent motorcycle managed to compare favorably with BMW and Zündapp among other. The Germans were not mistaken: the specimens caught at the end of the Phoney War were donated to the German units, some of them were even sent to fight on the Russian front...

Partnering with Air France

Thanks to its privileged relations with Hispano-Suiza, Yacco occupied a prominent place in the nascent airline industry. The excellent engines made by the builder from Bois-Colombes were used to equip most of the first aircrafts, Dewoitine D.338 - Marc Birkigt was among Emile Dewoitine’s main partners - Lioré & Olivier H-242 or Breguet T 393, which flew under the banner of the young Air France company. The prestigious airline was undoubtedly an excellent publicity.

However, beyond the media impact, the use of Yacco lube turned out to be essential to ensure the proper running of the engines. It was designed to meet very stringent technical requirements. The aircrafts used to run at very high speeds for hours and they needed to be reliable to ensure the flights and passengers safety. The slightest mechanical failure could lead to tragic consequences.

Marcel Doret

Legendary figure of the early stages of aviation, Marcel Doret was eighteen when the Great War broke out. With the status of temporary-career volunteer, he served for three years in the artillery before asking his assignment in aviation. He obtained his military pilot’s wings in 1918, after having studied at the School of Hunting and Acrobatics of Pau. His bold temper led the young pilot to become a test pilot at Dewoitine after the war. Pioneer of aerobatics, he performed the craziest stunts flying his famous red and yellow Dewoitine D.27, a fighter aircraft equipped with a Hispano-Suiza 300 hp engine. The fashion at the time was for airshows and Marcel Doret, undisputed star, moved large crowds. In 1927, Marcel Doret won an outstanding victory at the aerobatic meeting held at Dübendorf aerodrome near Zurich. Crowned "Air King" after the competition Marcel Doret was at the pinnacle of his career. Yacco found in him the ideal partner to praise the quality of its products.

The war

The end of the 1930s, rather gloomy, however announced the recovery of the economy as France was inevitably preparing for war. The Government bought more and more weapons, which thus stimulated the industry. In May 1938, Pierre Forgeot was appointed chairman of Yacco. The army was building up huge stocks of lube in preparation to the conflict. Consequently, the company had to install extra-large capacity tanks in its new plant in Rouen. Yacco experienced again a period of economic revival that was unfortunately short-lived! In May 1939, Maurice Dollfus resigned, too busy with the management of Ford SAF. France toppled into war in the autumn and activity slowed down. Thanks to the Standard Oil, Yacco obtained many contracts with Allied troops.

But, the German offensive of May 1940 put in peril the future of the company. The French military authorities set fire to the Rouen plant so that the invading troops could not take it. Yacco’s production capacity was completely burnt to ashes.

Pierre Forgeot resigned in December 1940, replaced Jean Dintilhac. The company, lacking of raw material supply, was found on the edge of bankruptcy. In March 1941, the Board of Directors met in Vichy, in what looked like headquarters, temporarily relocated in the small thermal resort. Deliveries of petroleum products, severely rationed, were then practically prohibited.

Jean Dintilhac tried somehow to steer the company towards other activities. He attempted to develop lube substitutes with vegetable-based products. Yacco researchers settled in Croisic, a small seaside resort of Loire-Atlantique. The revenues of 1944 are reduced to the smallest share: 9,255,645 French francs, against 17,877,013 French francs in 1943. The company is in bad shape when the Liberation of France happened. In December 1944, Jean Dintilhac had to bear the brunt of this troubled period and is ousted from the management board. The soul of Yacco, the instigator of speed records, suddenly disappeared from the scene, leaving behind the company he had helped to build...

Post-war period

André Marcellin replaced Jean Dintilhac as chairman while Marius Dasté became the CEO of the company. The family Forgeot was back into business with André, and then his brother Jacques, both soon appointed directors. The latter managed the Crédit commercial de publicité, one of Yacco’s main shareholders. Pierre Picard, a man of resistance (companion of the Liberation), also joined the board. He was president from February 1960 to March 1982. It was then a new and dynamic team that sought to raise the prestige of the firm. Yacco rose from the ashes in a few years...

The record-breaking 2 CV

In 1953, the Montlhéry speed ring hosted once again a record-breaking car, in the great tradition of the 1930s. It was a Citroën 2 CV - original choice if any - radically transformed by Barbot, an engineer. The capacity was reduced from 375 to 350 cm3 in order to compete in Class J. Driven by Barbot and Vinatier father and son (the young Jean then had a successful career at Alpine), the odd racecar hit the track on September 27. He ran at to 90.96 kph on average for twelve hours and at 85.02 kph for twenty-four hours. The small Citroën seized nine international records.

Successes in competition

Yacco was proud to claim some successes. A Monopole sports racing car (equipped with a Panhard engine) won the Performance Index at the 24 hours of Le Mans in 1952 (Hémard-Dussous crew) as well as a class victory in the 500-750 cm3 category. It broke the legendary Le Mans race over 116.758 kph on average.

In 1953, a powerful Jaguar XK 120 (Peignaux-Jacquin crew) won the Lyon-Charbonnières rally. Louis Chiron, the famous Monegasque champion, won the Monte-Carlo rally in a Lancia Aurélia. These achievements were abundantly publicized through advertising.

The DS saga

Yacco came closer to its legendary partner by sponsoring the double chevron brand at several emblematic competitions. With its excellent road handling and great performance in slippery conditions, the DS proved to be the ideally fitted for rallies. Paul Coltelloni was crowned European Champion in 1959 driving an ID 19. He won a stunning victory in Monte-Carlo and several class victories at the terrible Liège-Rome-Liège or at the Acropolis rally. Yacco then partnered with René Trautmann, at the pinnacle of his career. After a remarkable season, the iconic star driver of Citroën won the French Rally Championship in 1963.

Citroën had the wind in its sails and wanted to shine on big international competitions. Major road marathons such as the Baja 1000 or the very hard London-Mexico are very fashionable. The Quai de Javel decided to assemble a team of five cars for the 1970 edition. Yacco is obviously in the game, finding again René Trautmann. The operation met the expected success and René Trautmann won the race. The other four teams (including one female team) all managed to cross the finish line, reaching the third, seventh and twelfth ranks. The firm then sponsored two SMs, brought by Guy Verrier (in charge of the competition at Citroën) at the 24 Hours of Le Mans (24 Heures du Mans) in 1972.

Back to the 24 Hours of Le Mans

In 1973, Jean-Claude Andruet and Richard Bond took the start of the famous Le Mans rally at the behind the wheel of a superb Ferrari 365 GTB 4 Daytona, brought by the Belgian team of Francorchamps. They were ranked twentieth at an average speed of 153.877 kph. In 1979, Yacco supported the team of La Pierre du Nord which drove two B16 Chevron racecars equipped with a Chrysler Roc engine. Two beautiful sport racing cars that reflected the spirit of that time...

The achievements of the 1980s

Yacco got involved in the competition, by sponsoring Marc Sourd, winner of the French Hill Climb Championship (Championnat de France de la Montagne) in 1981 in a Martini Roc F2. This discipline used to be less publicized but still very popular, gathering an audience of insiders. Yacco also partnered with Daf, which brought to the Paris-Dakar in 1988 the huge Bull trucks of approx. 1000 cv. Magnificently driven by Jan de Rooy, these impressive vehicles proved to be almost as fast in pure speed as the legendary Peugeot 205 Turbo 16. In the area of trucks, Gérard Cuynet’s victory at the European Championship in 1988 in his Ford Cargo 1988 should also be noted. A non-exhaustive list as the number of victories - all disciplines and categories combined - is important...

Prolific partnership with Audi...

In the mid-1980s, the four rings brand is successful in competition, thanks to its exceptional Quattro and other 200 Turbo. Jacques Aïta won the rallycross France Championship in 1985, while Xavier Lapeyre won the Championnat de France Production the following year. Very good results for vehicles at the cutting edge of technology...

... And with Mercedes-Benz

The three-pointed star also won some victories in collaboration with Yacco. The excellent 190 E 2.3-liter 16-valve Mercedes was driven by Jacques Lafitte at the DTM (German Touring Car Masters) during the 1991 season, with Dany Snobeck as a teammate. The latter won the Andros Trophy twice, in 1992 and 1993.

Yacco brand's story of sporting successes does not end in the early 90s. For the last twenty years, many drivers, trainers and fanscontinue to forge Yacco's legend...